The Phenomenon of Polishness, an interview with Bolesław Orłowski

On the 3 May the Institute of National Remembrance released a documentary titled “The Phenomenon of Polishness”. It is a story about prof. Bolesław Orłowski, who has been researching and promoting Polish contributions to the development of world science and technology for years. Maciej Kwaśniewski interviews prof. Orłowski about his mission.

Maciej Kwaśniewski: What is the phenomenon of Polishness?

Bolesław Orłowski: It is not easy to answer. In November 2014 I wrote an article for the Rzeczpospolita daily, which I had been working on for two months, titled "The Phenomenon of Polishness". I had to thoroughly think it over to be well understood, considering it is a bit like patriotism - people understand it differently. Because it has many dimensions and can be understood in various ways. I highlighted a few important issues in there that seemed to be from a completely different era to young people - such as selflessness. It is precisely selflessness that is one of the characteristics that I include in this phenomenon of Polishness. In that article, I reminded that this trait probably originated from the gentlemanly mindset, according to which it was not befitting a nobleman to take money from anyone, except the king. On this occasion I presented a true story from the interwar period. As we know, trains must run on time, so the Polish Ministry of Communications sent one of the employees to Switzerland to buy Swiss watches for railwaymen. The official had a choice of several companies and after some time let the ministry know about the purchase options. The ministry ordered him to make his own choice. The official chose one of the manufacturers and, as was customary, received a commission from them. It was not in breach of any law. However, upon his return to Poland, the news about the commission also reached his friends and he simply stopped being invited to social gatherings. This social boycott continued until the outbreak of World War II.

MK: "Polish Contribution to Natural Sciences and Technology. A Dictionary of Polish and Poland-Related Explorers, Inventors and Pioneers of Mathematical, Natural and Technical Sciences" is a great four-volume work, edited by you and published by the Institute of National Remembrance, that tries to even out the image of the past that emerges from our encyclopaedias...

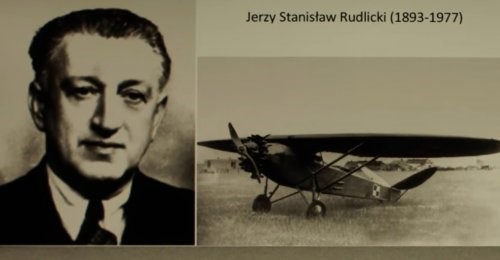

BO: I strive to show that Poles made a huge contribution to the development of many fields of knowledge. This applies, for example, to people active during the Great Emigration, but also to the Second Polish Republic, which was a particular curiosity in this field. For a country in the peripheries, we had an entirely unique situation here. People educated all over the world and those who had already gained recognition in the world of science returned to Poland. And this was despite Poland being a state with a rather frail economy at that time.

The dictionary contains approximately 1,300 biographical sketches. They were selected with respect to their originality, for example the first manufacturer of pharmaceutical products in Galicia. And also, of course, on account of belonging to the Polish nation. A person had to identify as a Pole. This is important, for example, in the United States, where among inventors and scientists of Jewish origin some felt Polish and others did not. One of those inventors made the first sound film. Another invented the transistor several decades before the Bell Foundation. They both felt Polish, wrote letters in the Polish language, and one of them, on leaving Poland, declared to the Polish military authorities that he could provide information on the new means of communication in the world.

MK: In how many countries did you find Polish scientists and technicians?

BO: In many. We had an exceptional situation in Turkey, but also in South America, for example in Peru, where apart from the railway builder Ernest Malinowski there was also Edward Jan Habich, the founder of the first polytechnic school in Latin America, in Lima. He had previously been a prominent participant in the January Uprising.

MK: Did you find anything surprising?

BO: Yes, especially about North America. Professor Sławomir Łotysz, who researched these matters based on, inter alia, records of the US Patent Office, established some facts that even the Polish diaspora did not know about. It was a tough job because nobody is capable of covering so many scientific fields in so many places. I had great collaborators who dealt with individual branches of science, such as prof. Andrzej Wróblewski or prof. Zbigniew Wójcik.

I would like to point out that the contribution to science and to the development of civilisation is now highly appreciated, and Poles should know about the scientific achievements of their ancestors, about the discoveries and the progress made thanks to them around the world.

MK: What is the message of the book?

BO: It is a tool for building the image of Poland in the world. Poland should popularise and promote people who helped develop other countries. An English version should also be issued. The contribution of Polish scientists to the victory of World War II exceeded our military contribution many times.

MK: Were we a scientific power?

BO: After 1939, many Polish scientists found themselves in the West, mainly in Great Britain. There were over 5,000 of them there alone and 4,400 worked in various structures of the armed forces. They were the authors of countless improvements to military equipment that gave an advantage to the Allies. For instance, the largest number of our accomplishments was related to the systems of communication. What is interesting, they were students of professor Janusz Groszkowski, the man who initiated Polish electronics in the 1920s and who was one of the pioneers of radars before the war. For example Józef Kosacki, who promoted the idea of an electromagnetic mine detector before the war and realised his idea in Great Britain in 1941. It was used for the first time at El Alamein and, in a modernised form, continued to be used until the 1990s. Another student of Groszkowski was Zygmunt Jelonek. He was the head of the British team that assembled the world's first radio line with eight communication channels, which was used during the Allied landings in Normandy. Wacław Struszyński - even before the war, in 1938 – filed an application with the Patent Office of the Republic of Poland for a patent for a certain direction finding system, but the war broke out and he found himself in England. Interestingly enough, this patent was granted to him by... the Office of the General Government in 1943. On the basis of this system, a radio direction finding antenna was constructed and used to detect German U-boats. Those vessels connected with their base at certain frequencies after surfacing. Then, thanks to Struszyński's device, they could be tracked down and destroyed. Several thousand such devices were produced and installed on all ships in Allied convoys. This system helped to win the Battle of the Atlantic. Rudolf Gundlach, on the other hand, was the inventor of the tank rotary periscope, with a viewing angle of 360 degrees. Curiously enough, Gundlach held a patent for it in several countries even before the war. It was most likely because of this fact that the device was widely used during the war, including by the Germans. No need to mention Enigma here.

MK: You say that you are a man of the Second Polish Republic.

BO: I was born in the Second Polish Republic. For this reason, I belong to a slightly different value system. As a young man, I remember the atmosphere of 1939 and the mood just before the outbreak of the Warsaw Uprising. I remember exactly that, in the shared consciousness of Poles, we could not yield to any of Hitler’s demands, and the Warsaw Uprising had to break out, because such was the pressure of the public opinion. I consider the insurgent tradition to be both important and useful.

MK: You show a different face, or better still – a different soul of Poles. Not romantic warriors, but rational scientists who build civilisation, albeit frequently in foreign countries.

BO: They are often the same people. From the moment when – for a certain part of Polish society, the more aware part – the question of regaining independence became important, or even the most important matter, all other issues were treated as less urgent. As a consequence, from the time of the Partitions of Poland, all those who fought for the Polish cause with arms in hand, or by writing about it, are all included in every Polish encyclopaedia. We know about them, or at least we should. The other type is absent from encyclopaedias. I mean those who, at that time, made inventions, built bridges and telegraph lines. For their contemporaries, it was less critical and has been lost to obscurity. For example, Ignacy Domeyko. We know him as someone important for Poland, but he is famous mainly on account of being a schoolmate of Adam Mickiewicz. However, we are less familiar with the fact that he was among the most prominent figures in the world of science in Chile. Or Karol Brzozowski, the famous poet, a participant in the Greater Poland uprising and the January Uprising, later in exile in Turkey. The Polish Biographical Dictionary describes all of his dramatic and poetic works, including a detailed discussion of plays that were staged only twice. But there are just two sentences about the fact that he built 40,000 kilometres of telegraph lines in the Ottoman Empire. That was the greatest achievement of his life.

MK: If you were to create a model of a Pole, what would be the ratio of the romantic warrior to the rationalist in that soul?

BO: Sometimes you have to be pragmatic in your patriotism, just like Stanisław Staszic. There are not many kinds of patriotism, you can be either patriotic or not. It is a matter of choice.

MK: Thank you for this interview.

Historical period: The Second Polish Republic (1922-1939)

Author: Maciej Kwaśniewski, Bolesław Orłowski, 4 May 2020